Hindu temple customs and etiquette

Any

Hindu Temple is a holy place designated for public worship of God, where the

form of God has been consecrated as per "Agama Shastra" (Procedures

and rites based on specific scripture dealing with temple construction and

worship). A temple is an essential part of the community and its presence is

expected add to the peace and tranquility of the locality.

Many

ancient temples are also rich treasure houses of traditional Indian art,

sculpture and architecture; they serve as museums too for the tourists to come,

view and appreciate the magnificent sculptural and architectural capabilities

of the artisans of the yore.

Whether

you are visiting a temple as a devotee or as a tourist, you should know how to

conduct yourself at the holy premises. You may be surprised to notice that in

reality even many of the devotees of God and the staff of the temple may not be

following some of the guidelines here, but that need not be an excuse for you

to ignore them.

In

most of the temples, the priests or pujaris belong traditionally to Brahmin

class. In most of the temples (particularly in south India), only pujaris are

allowed to touch the image if the God and do all the procedural worship

including bathing the idol, dressing up, conducting puja and archana and other

such practices. None other than the pujaris can enter the "Garbha

Gruha" (Sanctum Sanctorum - the cubicle in which the idol is placed and

worshiped).

In

a well maintained temple, worship is conducted 6 times a day. Food (Prasad) is

specially prepared for offering to God (at least twice a day) and the food is

distributed to the priests, employees and the devotees who visit the temple.

There

are many other customs and practices regularly followed in temples and there

will be many differences in them from one temple to another based on several

facts like who is the Prime God worshiped (like Shiva or Vishnu or other Gods),

the specific region or location of the temple, the specific cultural background

behind the origin of the temple and so on. Devotees are expected to honor the

specific customs followed in a specific temple, though it may be patently

different from those followed in some other temple.

Here are some etiquette to be followed by visitors to the

temple:

(1)

Switch of the cell phone, or leave the cell phone in your vehicle:

A

visit to the temple is essentially to get some peace and tranquility in you

from your hectic and distracting daily schedules and chores. Cell phones have

proved to be one of the greatest

"peace-disturbers"

and you will be better off without them at least during the few minutes of your

stay inside the holy temple premises.

(2)

Leave your foot-wear outside the temple:

Of

course, all Hindus know of this fundamental requirement. Outside prominent temples,

Foot-wear stands will normally be available (either run free or for a nominal

charge run by the temple authorities/ contractors).

(3)

Dress conservatively:

Women

should dress modestly when going to the temple. Wearing of traditional dresses

lile Saree or Salwar-Khamiz (or Churidar) which cover the entire body of the

woman is desirable.

As

for men, the general dress code is to avoid wearing colourful lungis; Grown ups

are advised not to wear Bermudas'. Wearing a traditional Dhoti' is desirable.

In south India (particularly at Kerala) going to temple bare-bodied above the

waist is considered a sign of humility shown before God. Many popular temples

in Kerala (like Guruvayur temple) insist that men-folk should remove their

upper garments before entering the temple.

Some

temples may have entry restricted to foreigners belonging to other religions.

It is always better to accept such restrictions rather than making an issue out

of it and creating a scene.

(4)

Observe personal cleanliness:

In

India, it is the general practice that people go to temple after taking bath.

Where the temple has a temple tank or where a river flows adjacent to the

temple, bathing can be done there (if you are used to taking bath in public).

Another

commonly practiced discipline in India is that women do not visit temples

during their menstrual periods.

(5)

Do not gossip, talk aloud, indulge in fun and frolic inside temple:

The

temple atmosphere must help you and others to elevate the minds from the

mundane to the spiritual. Using the temple as a place for get-together to make

fun, gossip or to discuss politics must be avoided.

(6)

Chant God's holy name, your Mantra or hymns:

It

is said that the holy atmosphere in the temple has the power to augment your

spiritual efforts. Chanting God's holy name, repeating your Mantra are reciting

sloka (holy hymns) are highly recommended. But make sure that you do not them

loudly to show off or to impress or distract others.

(8)

Keep the temple premises clean:

Never

throw off plastic bags, paper wastes, leaves, eatables, flowers, garlands,

coconut shells or fiber indiscriminately around the temple premises.

If

the temple has the practice of giving sanctified food (prasad) for eating, do

not throw it away ust in case it is unpalatable to you.

Where

prasads like Kumkum or sacred ash is given to you, do not throw the excess

stuff into the nearby recesses at the pillars and walls of the temple. Always

take a piece of paper with you and fold them and keep with you.

(9)

Maintain silence, decorum and reverence at the Sanctum sanctorum:

Where

there is a queue to reach the sanctum sanctorum, follow it; do not try to jump

the queue and gain an out of turn entry; make your prayers silently. In your

enthusiasm to devour the beauty of the divine form in full, do not obstruct the

view of those standing behind you. Do not yell out God's holy name too

emotionally which could disturb other devotees who are silently praying to God.

In

case of performing "archana" (special prayers) to the God, if the

temple has the system of buying tickets for it, follow the procedure; do not

short-cut the procedure by paying money discreetly to the priests.

If

the crowd is more, do not try to steal' more than your share of time in

standing before the deity at the cost of irritating the other devotees. Do not

get into argument with the temple staff members who are engaged in crowd

control, who normally display a tendency to behave rudely with the crowd.

(10)

Respect the regulations:

Be

it standing in a queue, or paying money to the priest, breaking coconut or

lighting a camphor, if the temple has certain regulations, observe them and do

not try to break the rules.

More

"don't"s

1.

Maintain decency of behaviour.

2.

Do not ogle the opposite sex;

3.

do not smoke, drink or chew tobacco

and betel leaves inside temple.

4.

Do not come into the temple in an

inebriated condition.

5.

Do not spit or urinate in secluded

corners.

6.

Do not utilize the exterior of the

compound walls of the temple or the steps around the temple tank as a public

toilet.

7.

Do not apply soap and wash cloth in

the temple tank. If you happen to be a local villager, do not take your cattle

to the temple tank to bathe them there.

8.

If you are visiting the temple as a

couple, you should never indulge in any nefarious behaviour treating the temple

gardens, secluded corners and tanks as though they are romantic places of

indulgence.

9.

Do not desecrate the ancient

sculptures and paintings. Nothing should be done knowingly or unknowingly to

cause any damage to the rich art forms available to us through generations in

the temples. Do not inscribe your name and your lover's name in temple walls,

pillars or tree trunks.

10.

The above guidelines are meant for

people who visit temples. Such disciplines (and perhaps even more stringent

ones) are equally applicable to the priests and employees inside the temple,

too.

Swami

Vivekananda says that the atmosphere inside a temple has subtle vibrations

conducive for getting mental peace and tranquility. Devotees should do their

best not to disturb those holy vibrations but to get benefited by them.

The Hindu Temple - Where Man Becomes God

Ancient Indian

thought divides time into four different periods. These durations are referred

to as the Krta; Treta; Dvapara; and Kali.

The first of these

divisions (Krta), is also known as satya-yuga, or the Age of Truth. This was a

golden age without envy, malice or deceit, characterized by righteousness. All

people belonged to one caste, and there was only one god who lived amongst the

humans as one of them.

In the next span

(Treta-yuga), the righteousness of the previous age decreased by one fourth.

The chief virtue of this age was knowledge. The presence of gods was scarce and

they descended to earth only when men invoked them in rituals and sacrifices.

These deities were recognizable by all.

In the third great

division of time, righteousness existed only in half measure of that in the

first division. Disease, misery and the castes came into existence in this age.

The gods multiplied. Men made their own images, worshipped them, and the

divinities would come down in disguised forms. But these disguised deities were

recognizable only by that specific worshipper.

Kali-yuga is the

present age of mankind in which we live, the first three ages having already

elapsed. It is believed that this age began at midnight between February 17 and

18, 3102 B.C. Righteousness is now one-tenth of that in the first age. True

worship and sacrifice are now lost. It is a time of anger, lust, passion,

pride, and discord. There is an excessive preoccupation with things material

and sexual.

From the

contemporary point of view, temples act as safe haven where ordinary mortals

like us can feel themselves free from the constant vagaries of everyday

existence, and communicate personally with god. But our age is individualistic

if nothing else. Each of us requires our own conception of the deity based on

our individual cultural rooting. In this context it is interesting to observe

that the word ‘temple,’ and ‘contemplate’ both share the same origin from the

Roman word ‘templum,’ which means a sacred enclosure. Indeed, strictly

speaking, where there is no contemplation, there is no temple. It is an irony

of our age that this individualistic contemplative factor, associated with a

temple, is taken to be its highest positive virtue, while according to the fact

of legend it is but a limitation which arose due to our continuous spiritual

impoverishment over the ages. We have lost the divine who resided amongst us

(Krta Yuga), which is the same as saying that once man was divine himself.

But this is not to

belittle the importance of the temple as a center for spiritual nourishment in

our present context, rather an affirmation of their invaluable significance in

providing succour to the modern man in an environment and manner that suits the

typical requirements of the age in which we exist.

Making

of the Temple

The first step

towards the construction of a temple is the selection of land. Even though any

land may be considered suitable provided the necessary rituals are performed

for its sanctification, the ancient texts nevertheless have the following to

say in this matter: “The gods always play where groves, rivers, mountains and

springs are near, and in towns with pleasure gardens.” Not surprisingly thus,

many of India’s ancient surviving temples can be seen to have been built in

lush valleys or groves, where the environment is thought to be particularly

suitable for building a residence for the gods.

No matter where it

is situated, one essential factor for the existence of a temple is water. Water

is considered a purifying element in all major traditions of the world, and if

not available in reality, it must be present in at least a symbolic

representation in the Hindu temple. Water, the purifying, fertilizing element

being present, its current, which is the river of life, can be forded into

inner realization and the pilgrim can cross over to the other shore

(metaphysical).

The practical

preparations for building a temple are invested with great ritual significance

and magical fertility symbolism. The prospective site is first inspected for

the ‘type,’ of the soil it contains. This includes determining its color and

smell. Each of these defining characteristics is divided into four categories,

which are then further associated with one of the four castes:

- White Soil:

Brahmin

- Red Soil: Kshatriya (warrior caste)

- Yellow Soil: Vaishya

- Black Soil: Shudra

- Red Soil: Kshatriya (warrior caste)

- Yellow Soil: Vaishya

- Black Soil: Shudra

Similarly for the

smell and taste:

- Sweet: Brahmin

- Sour: Kshatriya

- Bitter: Vaishya

- Astringent: Shudra (a reminder perhaps of the raw-deal which they have often been given in life)

- Sour: Kshatriya

- Bitter: Vaishya

- Astringent: Shudra (a reminder perhaps of the raw-deal which they have often been given in life)

The color and

taste of the soil determines the “caste” of the temple, i.e., the social group

to which it will be particularly favourable. Thus the patron of the temple can

choose an auspicious site specifically favourable to himself and his social

environment.

After these

preliminary investigations, the selected ground needs to be tilled and

levelled:

Tilling: When the

ground is tilled and ploughed, the past ceases to count; new life is entrusted

to the soil and another cycle of production begins, an assurance that the

rhythm of nature has not been interfered with. Before laying of the actual

foundation, the Earth Goddess herself is impregnated in a symbolic process

known as ankura-arpana, ankura meaning seed and arpana signifying offering. In

this process, a seed is planted at the selected site on an auspicious day and

its germination is observed after a few days. If the growth is satisfactory,

the land is deemed suitable for the temple. The germination of the seed is a

metaphor for the fulfilment of the inherent potentialities which lie hidden in

Mother Earth, and which by extension are now transferred to the sacred

structure destined to come over it.

Levelling: It is

extremely important that the ground from which the temple is to rise is

regarded as being throughout an equal intellectual plane, which is the

significance behind the levelling of the land. It is also an indication that

order has been established in a wild, unruly, and errant world.

Now that the earth

has been ploughed, tilled and levelled, it is ready for the drawing of the

vastu-purusha mandala, the metaphysical plan of the temple.

The square shape is symbolic of earth, signifying the four directions which bind and define it. Indeed, in Hindu thought whatever concerns terrestrial life is governed by the number four (four castes; the four Vedas etc.). Similarly, the circle is logically the perfect metaphor for heaven since it is a perfect shape, without beginning or end, signifying timelessness and eternity, a characteristically divine attribute. Thus a mandala (and by extension the temple) is the meeting ground of heaven and earth.

These considerations make the actual preparation of the site and laying of the foundation doubly important. Understandably, the whole process is heavily immersed in rituals right from the selection of the site to the actual beginning of construction. Indeed, it continues to be a custom in India that whenever a building is sought to be constructed, the area on which it first comes up is ceremonially propitiated. The idea being that the extent of the earth necessary for such construction must be reclaimed from the gods and goblins that own and inhabit that area. This ritual is known as the ‘pacification of the site.’ There is an interesting legend behind it:

This vastu-purusha

is the spirit in mother-earth which needs to be pacified and is regarded as a

demon whose permission is necessary before any construction can come up on the

site. At the same time, care is taken to propitiate the deities that hold him

down, for it is important that he should not get up. To facilitate the task of

the temple-architect, the vastu-mandala is divided into square grids with the

lodging of the respective deities clearly marked. It also has represented on it

the thirty-two nakshatras, the constellations that the moon passes through on

its monthly course. In an ideal temple, these deities should be situated

exactly as delineated in the mandala.

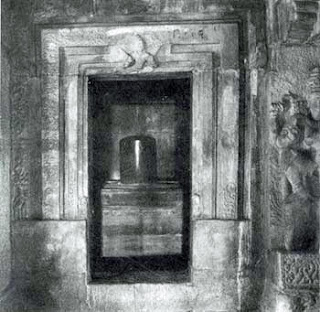

Sanctum of a Hindu Temple |

In the central

grid of the vastu-mandala sits Brahma, the archetypal creator, endowed with

four faces looking simultaneously in all directions. He is thus conceived as

the ever-present superintending genius of the site. At this exact central point

is established the most important structure of the sacred complex, where the

patron deity of the temple is installed. Paradoxically this area is the most

unadorned and least decorated part of the temple, almost as if it is created in

an inverse proportion to its spiritual importance. Referred to as the sanctum

sanctorum, it is the most auspicious region in the whole complex. It has no

pillars, windows or ventilators. In addition to a metaphysical aspect, this

shutting off of air and light has a practical side to it too. It was meant to

preserve the icon, which, in olden days, was often made of wood. Also, besides

preventing the ill effects of weathering, the dark interior adds to the mystery

of the divine presence.

Throughout all

subsequent developments in temple architecture, however spectacular and

grandiose, this main shrine room remains the small, dark cave that it has been

from the beginning. Indeed it has been postulated (both by archaeology and

legend), that the temple developed from the cave-shrine of the extremely remote

past. This is another instance in Hinduism where the primitive and the modern,

along with all the developments in-between, can be seen to co-exist remarkably

and peacefully.

When the devotee

enters a temple, he is actually entering into a mandala and therefore

participating in a power-field. The field enclosures and pavilions through

which he must pass to reach the sanctum are symbolic. They represent the phases

of progress in a man’s journey towards divine beatitude. In accordance with

this scheme of transition, architectural and sculptural details vary from phase

to phase in the devotee’s onward movement, gradually preparing him for the

ultimate, awesome experience, which awaits him in the shrine.

This process

mirrors the four-phased spiritual evolution envisaged in yoga, namely the

waking state (jagrat); dream state (swapna); the state of deep sleep

(sushupti); and finally the Highest state of awareness known in Sanskrit as

turiya. This evolution takes place as follows:

On reaching the

main gateway, the worshipper first bends down and touches the threshold before

crossing it. This marks for him the fact that the transition from the way of

the world to the way of god has been initiated. Entering the gateway, he or she

is greeted by a host of secular figures on the outer walls. These secular

images are the mortal, outward and diverse manifestations of the divinity

enshrined inside. In this lies a partial explanation behind the often explicit

erotic imagery carved on the outer walls of temples like those at Khajuraho,

where the deity inside remains untouched by these sensuous occurrences. Such

images awaken the devotee to his mortal state of existence (wakefulness). The

process of contemplation has already begun.

As he proceeds, carvings of mythological themes, legendary subjects, mythical animals and unusual motifs abound. They are designed to take one away from the dull and commonplace reality, and uplift the worshipper to the dreamy state.

Chhapri Temple, Central India The immediate

pavilion and vestibule before the icon are restrained in sculptural

decorations, and the prevailing darkness of these areas are suggestive of

sleep-like conditions.

|

Finally the

shrine, devoid of any ornamentation, and with its plainly adorned entrance,

leads the devotee further to the highest achievable state of consciousness,

that of semi-tranquillity (turiya), where all boundaries vanish and the

universe stands forth in its primordial glory. It signifies the coming to rest

of all differentiated, relative existence. This utterly quiet, peaceful and

blissful state is the ultimate aim of all spiritual activity. The devotee is

now fully-absorbed in the beauty and serenity of the icon. He or she is now in

the inner square of Brahma in the vastu- mandala, and in direct communion with

the chief source of power in the temple.

The thought behind

the design of a temple is a continuation of Upanishadic analogy, in which the

atman (soul or the divine aspect in each of us) is likened to an embryo within

a womb or to something hidden in a cave. Also says the Mundaka Upanishad: ‘The

atman lives where our arteries meet (in the heart), as the spokes of the wheel

meet at the hub.’ Hence, it is at the heart center that the main deity is

enshrined. Befittingly thus, this sanctum sanctorum is technically known as the

garba-griha (womb-house).

The garbhagriha is

almost always surrounded by a circumambulatory path, around which the devotee

walks in a clockwise direction. In Hindu and Buddhist thought, this represents

an encircling of the universe itself.

No description of the Hindu temple can

be complete without a mention of the tall, often pyramid-like structure

shooting up the landscape and dominating the skyline.

This element of temple

architecture is known as ‘shikhara,’ meaning peak (mountain). It marks the

location of the shrine room and rises directly above it. This is an expression

of the ancient ideal believing the gods to reside in the mountains. Indeed, in

South India the temple spire is frequently carved with images of gods, the

shikhara being conceived as mount Meru, the mythical mountain-axis of the

universe, on the slopes of which the gods reside.

|

Temple of Mahabodhi, Bodhgaya |

In North India too, it is worthwhile

here to note, most goddess shrines are located on mountain tops. Since it rises

just above the central shrine, the shikhara is both the physical and spiritual

axis of the temple, symbolizing the upward aspiration of the devotee, a potent

metaphor for his ascent to enlightenment.

Conclusion

Man lost the divinity within himself.

His intuition, which is nothing but a state of primordial alertness, continues

to strive towards the archetypal perfect state where there is no distinction

between man and god (or woman and goddess). The Hindu Temple sets out to

resolve this deficiency in our lives by dissolving the boundaries between man

and divinity. This is achieved by putting into practice the belief that the

temple, the human body, and the sacred mountain and cave, represent aspects of

the same divine symmetry.

Truly, the most modern man can survive

only because the most ancient traditions are alive in him. The solution to

man’s problems is always archaic. The architecture of the Hindu temple

recreates the archetypal environment of an era when there was no need for such

an architecture.